The Night of the Iguana

In the film’s opening scene Episcopal clergyman T. Lawrence Shannon is having a “nervous breakdown” after being ostracized by his congregation and defrocked for having an inappropriate relationship with a “very young Sunday school teacher.”

Two years later, Shannon, now a tour guide for the bottom-of-the-barrel Texas company Blake’s Tours, is taking a group of Baptist schoolteachers by bus to Puerto Vallarta. The group’s leader Miss Judith Fellowes is concerned about her 16-year-old niece Charlotte Goodall who is attracted to Shannon. During a road break while Shannon and Charlotte go swimming, Fellowes becomes hysterical, yelling at them from the shore. She then accuses Shannon of trying to seduce Charlotte and is intent on reporting him to his employer.

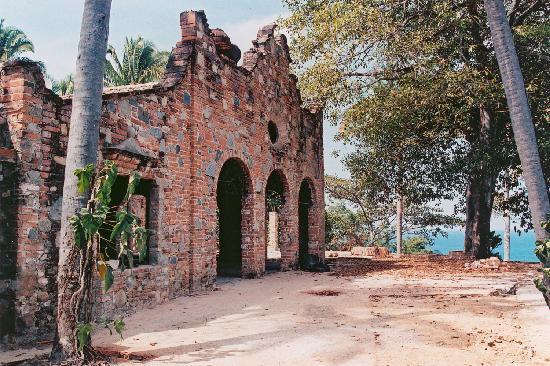

Before reaching the group’s hotel, Shannon suddenly veers off and recklessly drives the terrified passengers to a cheap Costa Verde hotel in Mismaloya, and removes the distributor cap from the engine. The hotel had been run by his old friend Fred, but Shannon learns from Fred’s widow, Maxine of his passing. Shannon convinces her to allow the tour group to stay at the hotel, believing that Miss Fellowes will be unable to reach a phone.

Another arrival at the hotel is Hannah Jelkes, a celibate sketch artist from Nantucket traveling with her elderly poet grandfather Nonno who performs live readings wherever they go. They have run out of money, but Shannon convinces a distrustful Maxine to let them have a room.

Over a long night Shannon wards off Charlotte’s advances when she slips into his room. Miss Fellowes’ bangs on the door and further threatens Shannon. The following day she’s contacted the travel agency and lets Shannon know that he’s ruined. She reminds him, back in Texas her brother is a judge.

Shannon now “at the end of his rope,” like the iguana kept tied by Maxine’s cabana boys, suffers a breakdown. The cabana boys truss him in a hammock, while Shannon rages. Hannah brings tea and consoles him. She persuades Shannon to free the iguana from its rope.

Hannah’s grandfather has an epiphany and delivers the poem he had been struggling to finish — about having heart in a corrupt world. As Hannah tells him how beautiful his poem is, he passes. Maxine is puzzled by the meaning of the poem but deeply moved.

In the morning the distributor cap is retrieved and Miss Fellows and the rest of the tour group set out to leave. Miss Fellows threatens Shannon, but Maxine starts to tell off Miss Fellows, alluding to her repressed lesbian feelings for Charlotte. Miss Fellows looks confused and caught off-guard. Shannon stops Maxine from saying anything further. “Just go” he says to Miss Fellows. He later explains to Hannah that Maxine’s revelation would have broken Miss Fellows. Hannah is struck by Shannon’s sparing act of kindness to his nemesis.

Sensing the bond between the two of them, Maxine offers to turn the hotel over to Hannah and Shannon, but Hannah rejects that offer and parts ways.

Shannon will stay. Maxine proposes they go down to the beach. Shannon says “I can get downhill but I’m not too sure about getting back up.” Maxine turns to him smiling, “I’ll get you back up, baby. I’ll always get you back up.”

Production and release

James Garner claimed that he was originally offered the role played by Richard Burton, but he declined because “it was just too Tennessee Williams for me.” On the other hand, Richard Burton was perfectly suited for the role of Rev. T. Lawrence Shannon—described as “funny, drunk, with an underlying kindness…handsome, spirited, and a little nuts.”

In September 1963, Huston, Lyon and Burton, accompanied by Elizabeth Taylor, arrived at Puerto Vallarta—a “remote little fishing village”—for principal photography in Mismaloya, which lasted 72 days. Huston liked the area’s fishing so much that he bought a $30,000 house “in a cottage colony eight miles outside town.”

By March 1964, months before the film’s release, gossip about the film’s production was widespread. Huston received a Writers Guild of America award for advancing “the literature of the motion picture through the years.” At the award dinner, Allan Sherman performed a song to the tune of “Streets of Laredo” with lyrics that included:

“They were down there to film The Night of the Iguana

with a star-studded cast and a technical crew.

They did things at night midst the flora and fauna

that no self-respecting iguana would do.”

The film won the 1964 Academy Award for Best Costume Design, and was nominated for the Academy Awards for Best Art Direction and Best Cinematography. Actress Grayson Hall received Academy Award and Golden Globe nominations for Best Supporting Actress, and Cyril Delevanti received a Golden Globe nomination for Best Supporting Actor. In addition to Delevanti’s nomination at the Golden Globes, Ava Gardner also received a Best Actress in a Motion Picture – Drama nomination. Both the picture and its director, John Huston, likewise received Golden Globe nominations. The film grossed $12 million worldwide at the box office, earning $4.5 million in U.S. theatrical rentals. It was the 10th highest-grossing film of 1964.

Time magazine’s reviewer wrote, “Huston and company put together a picture that excites the senses, persuades the mind, and even occasionally speaks to the spirit—one of the best movies ever made from a Tennessee Williams play.”